View from The Hill: Coronavirus hits at the heart of Morrison’s government, with Peter Dutton infected

View from The Hill: Coronavirus hits at the heart of Morrison’s government, with Peter Dutton infected

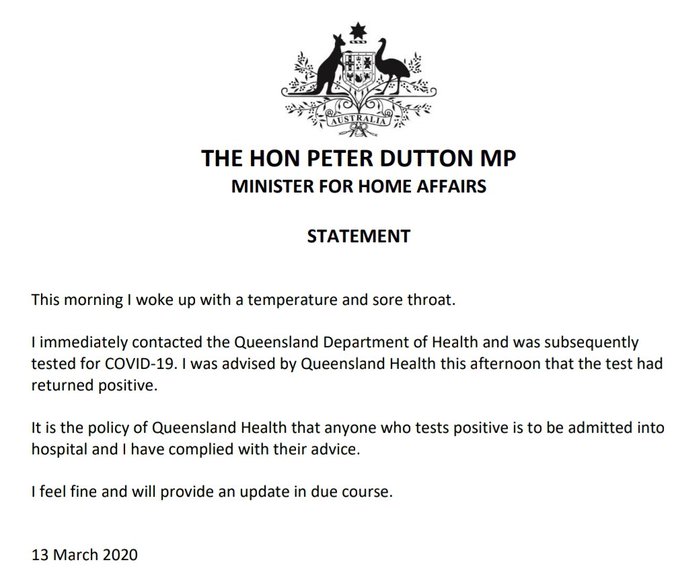

It was a sensational day in the ever-escalating coronavirus story, with Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton on Friday testing positive for COVID-19 and admitted to hospital.

Meanwhile, sporting and other organisations prepared for massive changes, after the government’s announcement of the latest moves to try to contain the spread of the virus.

In a sweeping set of measures, based on medical advice and unveiled by Prime Minister Scott Morrison following a meeting of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), organisations have been advised against mass gatherings of 500 people or more, a national cabinet of federal and state leaders is being formed, and Australians are being told not to travel abroad unless they really need to.

The revelation about Dutton - who recently visited the United States - threw the Prime Minister’s Office into a spin. Dutton had attended cabinet on Tuesday. Did this mean he could have infected the whole upper echelon of the government as a job lot?

Well, no, came the word from the PMO. The medical advice was that only people who’d had close contact with Dutton in the 24 hours before he showed symptoms needed to self-isolate.

The latest indication is the Prime Minister doesn’t plan to be tested, because he doesn’t need to be. But don’t take that for gospel. Everything can change in a few hours. For example, on Friday afternoon Morrison was proposing to go to the football on Saturday; on Friday night he wasn’t.

The coronavirus crisis is moving so fast that by Friday, the government’s $17.6 billion stimulus package, critically important though it is, seemed very much Thursday’s news.

Read more: Viral spiral: the federal government is playing a risky game with mixed messages on coronavirus

On Friday morning, praise for the government’s handling of the crisis suddenly seemed to be changing into criticism, with attention shifting sharply from economics to health and questions mounting. Why was it so tardy with its advertising campaign? Where was the “clear plan” it said it had to deal with the virus and was it adequate?

By mid-afternoon Friday – and a few hours after the Melbourne Grand Prix was cancelled – the dramatic new stage of the fight against COVID-19 started to unfold.

According to the Prime Minister’s Office, the “national cabinet” - a sort of health war cabinet - has no precedent in Australian history. To meet weekly from Sunday, it is a too-rare example of the federation working at its best, across state boundaries and party lines. In this highly complex situation, maximum co-ordination of effort and resources is vital.

The advice on mass gatherings - to apply from Monday – had seemed inevitable sooner or later. Critics were saying it should have been already in place. It is not a formal ban, but that’s unlikely to be necessary. What organisation would fly in the face of the recommendation?

Both Morrison and Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy were at pains to say this action was being taken early, to keep ahead of the rapidly evolving situation.

“This is a scalable response,” said Morrison. “What we’re doing here is taking an abundance-of-caution approach”.

“What we’re seeking to do is lower the level of overall risk and at the same time ensure that we minimise any broader disruption that is not necessary at this stage.”

“There is every reason for calm,” he insisted, even as the general community becomes, understandably, increasingly alarmed.

Earlier Morrison told Alan Jones: “I think it’s important for our economy and just our general well-being … that people sort of get on about their lives, you know, ‘keep calm and carry on’ is the saying.”

The government cannot avoid the inherent conflict between the duelling imperatives of health considerations and economic ones.

The greater the restrictions, even voluntary ones, on activity, the worse for the economy.

Some people might have spent at least part of their $750 cash handout from the stimulus on attending sporting events and the like.

More generally, while ramping up the protection measures is designed to make people not just safer but also feel safer, it equally could make them more anxious.

That could not just be a disincentive for individuals to spend their handouts, but also discourage businesses from buying new equipment, or even hanging onto workers, despite the encouragement they are being given.

The attempt to contain the spread of the virus for as long as possible is vital for the health system. An early big surge could overwhelm the intensive care facilities, which will cope much better if admissions are stretched over an extended period.

But for the economy, extending the duration in this manner worsens the impact.

This is an indication of the “wicked problem” the coronavirus is. Every policy response may produce some negative reactions, as well as the desired ones.

On some fronts the governments are trying to hold the line. They are not, for example, recommending schools or universities shut. A distinction is being made between “non-essential” gatherings and essential activities, like going to school or work.

In practice schools – which come under state responsibility – are shutting down on an individual basis for varying lengths of time when cases of the virus are discovered.

The Dutton diagnosis has raised the question the government hasn’t wanted to confront - how the parliament handles the outbreak when it spreads to one of its own.

Parliament resumes the week after next, with the priority to pass the legislation for the stimulus. It then adjourns until the May budget.

Asked on Friday about the implications of the “mass gatherings” edict for parliament, Morrison said parliament fell into the “essential” category but he flagged that visitors to the public galleries might be banned.

At that stage, Dutton’s illness had not become public.

It should be remembered that parliament doesn’t just belong to the government - making the question of its coming sittings still a live issue.

Courtesy:hThe conversation

Comments