Melting glaciers spell more disaster for China and South Asia

A landmark report highlights the threats of glacier retreat in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, writes Omair Ahmad

Imja Lake, one of the biggest glacial lakes in the Everest region of Nepal, is expanding with climate change (Image: Nabin Baral)

Glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region could lose over a third of their volume by 2100 even if the world manages to keep global warming below 1.5C, according to a report by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

If the global average temperature hits 2C then 49% of the volume of these glaciers will be lost.

The findings from the Hindu Kush Himalayan Monitoring and Assessment Programme (HIMAP) report looked at 16 components of change in the region, filling in gaps left by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The region, which is known as Asia’s water tower, is the source of ten major rivers, including the Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus, Mekong, Yellow River and Yangtze. The Himalayan and Tibetan Plateau is already warming at three times the global average. Since the 1970s, 15% of the ice has gone.

The retreat of these glaciers will have an immediate impact on the 240 million people that live in the mountains, many of whom are critically dependent on the water from snow and ice melt.

Downstream regions, which are inhabited by 1.9 billion people, will also face problems. One of the most affected basins will be the Indus, which is shared by China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The Indus River is most dependent on snowmelt and glacier melt, which contribute close to 80% of its water. In comparison, the Ganges and Brahmaputra, known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in China, are mostly dependent on runoff from rainfall. As the glaciers retreat at a sharper pace, the Indus basin will have more water flowing in, but it will be less predictable.

Tobias Bolch, from the University of Zurich’s geography department and one of the contributing lead authors of the chapter on the cryosphere in the Hindu Khush Himalayan region said, “The Indus glaciers span a large region. In the Karakoram range there is a mass balance [the glaciers are gaining as much ice as they lose], but that is a mix of melting and rapid advance of some glaciers. This increases the risk of Glacier Lake Overflow Floods. In Lahaul Spiti [in the western Himalayas of India], on the other hand, you have rapid glacier retreat, and this destabilises the land from where the glaciers retreat.”

He added that the cryosphere was not just the glaciers. The melting of permafrost – perennially frozen ground beneath the surface – as glaciers retreat will also destabilise the mountains.

According to Arun Bhakta Shrestha, the regional progamme manager for river basins and cryosphere at ICIMOD, the Indus region is also one of the areas of most concern for rainfall as well. Although the science on the western disturbance which affects the South Asian monsoon remains unclear, it is already evident that rainfall patterns have become more uneven, with an increase in extreme weather events.

More disasters, dangerous dams

The Indus basin is already one of the most affected by extreme weather events in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, with the most people killed from 1980 to 2015. These risks are likely to worsen because of dam and hydropower projects that are planned or being built. This includes hydro projects in Pakistan that are supported by China under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project.

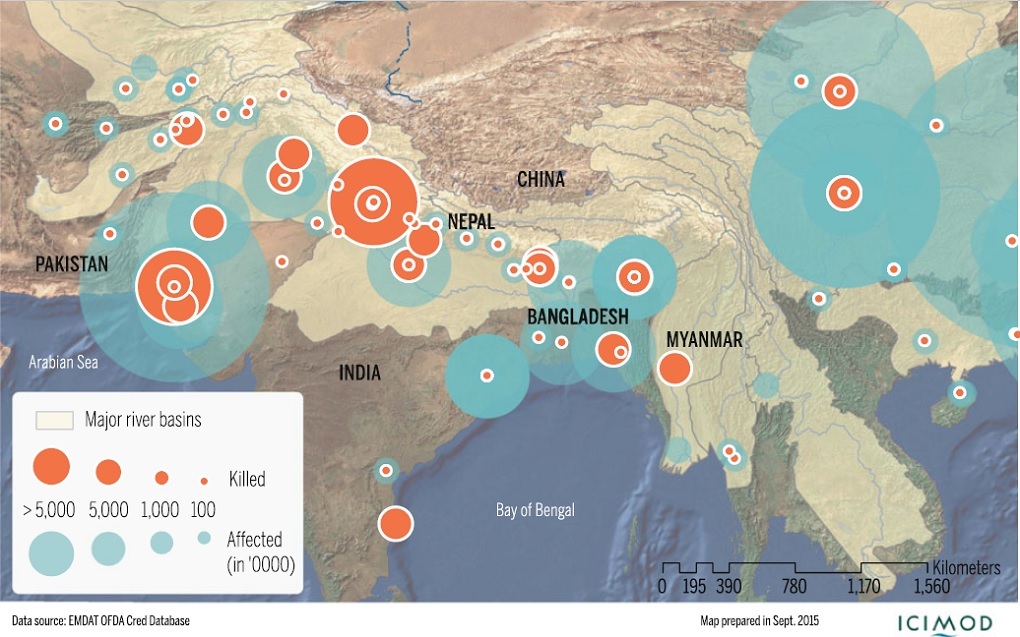

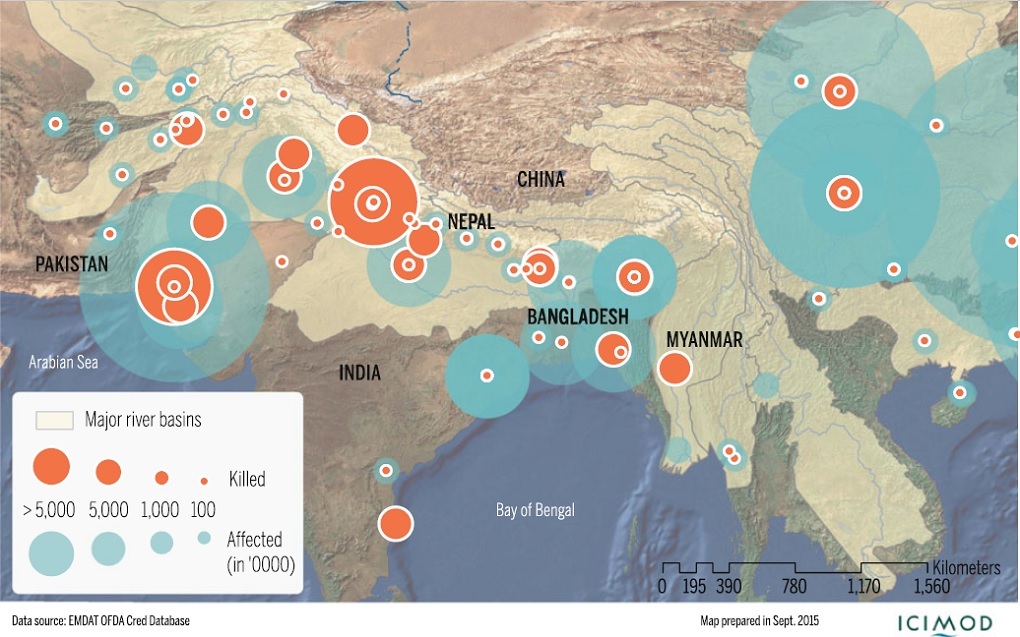

Extent and impact of flood disasters in river basins originating in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region from 2010-14 (Source: EM-DAT/CRED)

With sustained or increased water flow expected in the rivers until at least 2050, it is unlikely that planned dam projects will we reassessed. Indeed, the variation of water flows will be a boost to those in favour of large water storage projects to stabilise availability over the year.

Unfortunately the history of hydropower projects in South Asia – and elsewhere – has been marked by a lack of regard for environmental safeguards. Moreover, in India alone, indigenous communities, accounting for only 8% of the population, have accounted for 40% of those displaced by large dams, primarily because they live in mountainous regions.

Compounding the problem for the Indus basin is the difficult relationships between the four countries that share it: China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Given the stark threat to the whole basin and the people that live within it, development plans would ideally incorporate findings for the entire area, with coordination of disaster management plans, too.

Some have called for an expansion of the Indus Waters Treaty to include China and Afghanistan to better deal with these issues. But with the treaty itself under strain, there would seem to be limited scope for this to happen.

The HIMAP report should act as a warning for those living in the Indus basin, and spur a conversation on key issues of development planning. Unfortunately, the report also makes clear that geographically precise information from mountainous regions remains sparse. This is because decision-making for mountain areas is still largely controlled by policymakers in the plains. Until and unless that changes, the Indus will continue to be a river of disasters.

This article is republished from The Third Pole

Courtesy chinadialogue

If the global average temperature hits 2C then 49% of the volume of these glaciers will be lost.

The findings from the Hindu Kush Himalayan Monitoring and Assessment Programme (HIMAP) report looked at 16 components of change in the region, filling in gaps left by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The region, which is known as Asia’s water tower, is the source of ten major rivers, including the Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus, Mekong, Yellow River and Yangtze. The Himalayan and Tibetan Plateau is already warming at three times the global average. Since the 1970s, 15% of the ice has gone.

The retreat of these glaciers will have an immediate impact on the 240 million people that live in the mountains, many of whom are critically dependent on the water from snow and ice melt.

Downstream regions, which are inhabited by 1.9 billion people, will also face problems. One of the most affected basins will be the Indus, which is shared by China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The Indus River is most dependent on snowmelt and glacier melt, which contribute close to 80% of its water. In comparison, the Ganges and Brahmaputra, known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in China, are mostly dependent on runoff from rainfall. As the glaciers retreat at a sharper pace, the Indus basin will have more water flowing in, but it will be less predictable.

Tobias Bolch, from the University of Zurich’s geography department and one of the contributing lead authors of the chapter on the cryosphere in the Hindu Khush Himalayan region said, “The Indus glaciers span a large region. In the Karakoram range there is a mass balance [the glaciers are gaining as much ice as they lose], but that is a mix of melting and rapid advance of some glaciers. This increases the risk of Glacier Lake Overflow Floods. In Lahaul Spiti [in the western Himalayas of India], on the other hand, you have rapid glacier retreat, and this destabilises the land from where the glaciers retreat.”

He added that the cryosphere was not just the glaciers. The melting of permafrost – perennially frozen ground beneath the surface – as glaciers retreat will also destabilise the mountains.

According to Arun Bhakta Shrestha, the regional progamme manager for river basins and cryosphere at ICIMOD, the Indus region is also one of the areas of most concern for rainfall as well. Although the science on the western disturbance which affects the South Asian monsoon remains unclear, it is already evident that rainfall patterns have become more uneven, with an increase in extreme weather events.

More disasters, dangerous dams

The Indus basin is already one of the most affected by extreme weather events in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, with the most people killed from 1980 to 2015. These risks are likely to worsen because of dam and hydropower projects that are planned or being built. This includes hydro projects in Pakistan that are supported by China under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project.

Extent and impact of flood disasters in river basins originating in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region from 2010-14 (Source: EM-DAT/CRED)

With sustained or increased water flow expected in the rivers until at least 2050, it is unlikely that planned dam projects will we reassessed. Indeed, the variation of water flows will be a boost to those in favour of large water storage projects to stabilise availability over the year.

Unfortunately the history of hydropower projects in South Asia – and elsewhere – has been marked by a lack of regard for environmental safeguards. Moreover, in India alone, indigenous communities, accounting for only 8% of the population, have accounted for 40% of those displaced by large dams, primarily because they live in mountainous regions.

Compounding the problem for the Indus basin is the difficult relationships between the four countries that share it: China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Given the stark threat to the whole basin and the people that live within it, development plans would ideally incorporate findings for the entire area, with coordination of disaster management plans, too.

Some have called for an expansion of the Indus Waters Treaty to include China and Afghanistan to better deal with these issues. But with the treaty itself under strain, there would seem to be limited scope for this to happen.

The HIMAP report should act as a warning for those living in the Indus basin, and spur a conversation on key issues of development planning. Unfortunately, the report also makes clear that geographically precise information from mountainous regions remains sparse. This is because decision-making for mountain areas is still largely controlled by policymakers in the plains. Until and unless that changes, the Indus will continue to be a river of disasters.

This article is republished from The Third Pole

Courtesy chinadialogue

Comments