To mark World Water Day we take a look at some of China’s most culturally important but environmentally threatened lakes

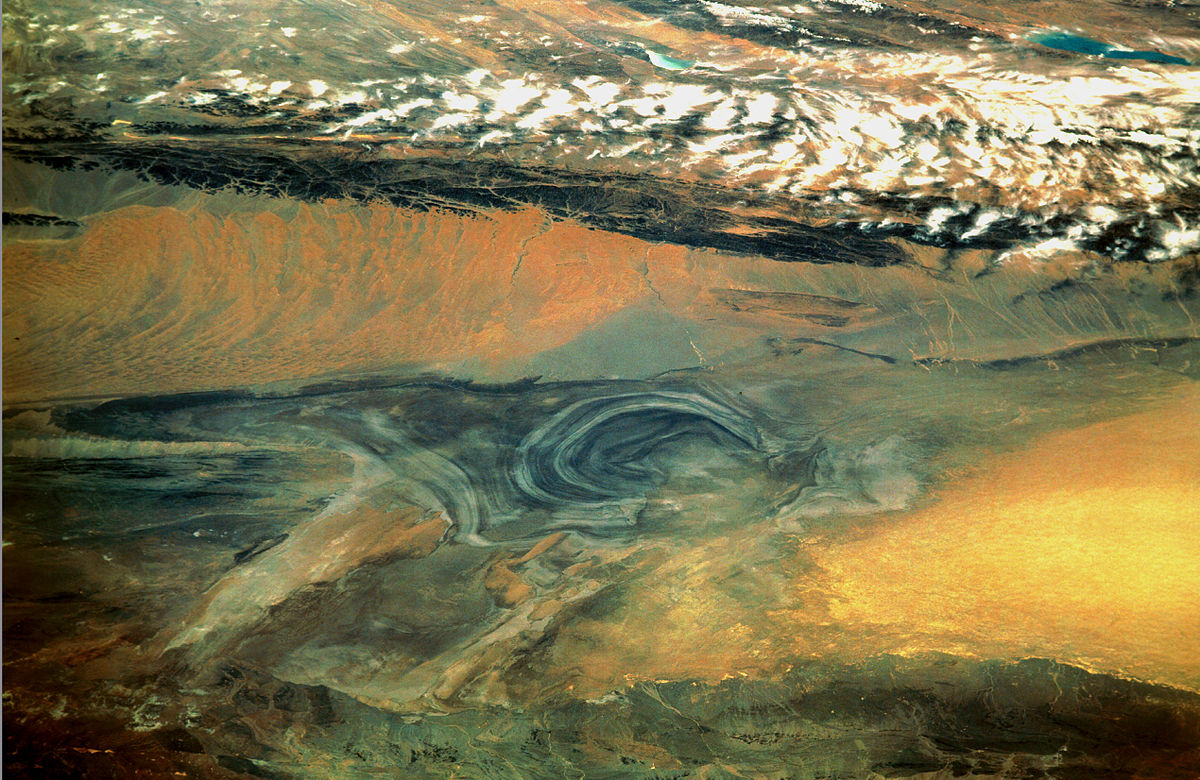

Take a trip around some of China's most interesting lakes, from the mysterious disappearance of Lop Nur to the remarkable recovery of Qinghai Lake (Image: NASA)

China’s rivers, lakes and seas are an important part of the country’s cultural geography, with the phrase “five lakes, four seas” meaning something akin to “from all over the country”.

But most of the country's lakes are in a state of crisis. China has a much smaller freshwater resource by population than many other nations, and those resources are both shrinking and threatened by pollution. Not only is China the world’s largest user of fertilizers, its water-polluting industries such as textiles and paper-making are huge, and both agriculture and industry have enormous water footprints.

Here, we include a couple of China’s traditional “five lakes” in the central and eastern parts of the country, but also include others that may not have the same cultural importance but which remain valuable ecosystems.

Click image above to explore China's lakes

Poyang Lake – to dam or not to dam

Despite being known as China’s largest freshwater lake, Poyang has no fixed size. The lake is huge, shallow and connected to the Yangtze, which means that every year its size fluctuates in line with the height of the river, shifting wildly from between 3,000 to only 100 square kilometres. For this reason it is known for becoming a wide expanse of clear water when in flood but little more than a river in the dry season.

But though Poyang shrinks during the dry season, it still provides a crucial habitat for migrating birds, which arrive here in autumn from Siberia to rest over the winter.

Yet for a decade now, Poyang has been experiencing earlier and longer dry seasons, and unusually low water levels. In extreme cases the locals have seen water supplies cut off entirely. Climate change is one reason, but the role of the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s biggest hydropower project, has also come in for scrutiny.

The office in charge of the lake’s water management system plans to build a barrier between the Yangtze and Poyang Lake to address the problem. But opponents say this will block migrating fish, and higher water levels will cause problems for the birds – resulting in ecological disaster. There is also a question over whether or not retaining more water in the lake will affect water security for cities downstream. The debate looks set to continue.

Qinghai Lake – back from rock bottom

Qinghai Lake is a saltwater lake situated in the north-east of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, and is China’s largest. But unlike other lakes that are shrinking, Qinghai seems to be recovering, with water levels increasing in recent years.

The provincial authorities have monitored the lake area since 1974, finding that in 2005 it had shrunk by 253 square kilometres, to 5.67% of its size in 1974. chinadialogue expressed concern about the risk to the lake a decade ago. But since 2005 the lake has, unexpectedly, been recovering. By 2016 it was almost back to its 1974 size, the largest recorded.

In February 2017 a provincial survey found the environment of the Qinghai Lake basin was well protected. The management bureau for the Qinghai Lake National Nature Reserve says that alongside interventions, such as returning farmland to forests and pastures and restoration of vegetation, another important factor is increased precipitation and glacier melt resulting from climate change. It’s ironic that while changing weather patterns are threatening low-lying islands and coastal areas, China’s largest lake is actually benefiting.

Ulunsuhai Nur

Situated in Inner Mongolia, Ulunsuhai Nur is home to 200 types of bird and is the highest wetland at this latitude. Strictly speaking, the lake is manmade, and was formed by efforts to redirect water from the Yellow River. Today, 80% of its water is directed through agricultural irrigation systems nearby, with the rest coming from rainfall.

From 1965 to 1975 local people constructed a modern drainage system between the Yellow River, farmland and Ulunsuhai Nur, to ensure water from irrigation would flow quickly into the lake where vegetation and microorganisms would break down fertilizer run-off. The “purified” water is then returned to the Yellow River.

That system of irrigation and drainage made the plains around Ulunsuhai Nur one of northern China’s most important agricultural regions, while the recovery of water from agriculture made the lake – which should be arid – a paradise for birds and a tourist hot spot.

But the system is today on the brink of failure. Experts point out that fertilizer use in China has increased 55-fold in 40 years, and Ulunsuhai Nur can no longer cope. For about ten years the lake has seen algal blooms during some summers resulting from eutrophication. This has worsened the water quality and affected the entire ecosystem, from birds to fish.

Lop Nur – the Sea of Death

Look down from the air and you can see the ear-like shape of Lop Nur, once a large lake but now dried up. In the 1920s it was estimated to be 3,000 square kilometres in size – twice as large as Beijing today. In 1959, it was still possible to sail a boat on it. It’s unclear when the lake dried up exactly, but the region is incredibly arid and once the rivers stopped flowing, Lop Nur, which was only three or four metres deep, may have dried up in a matter of years.

The lake has always had a legendary quality. Sven Anders Hedin, a Swedish explorer in the early 20th century, “discovered” it while travelling through the desert. Archaeologists later excavated relics and determined that it would have been an important oasis and stop on the Silk Road. It’s also claimed the lives of a number of explorers, including two famous Chinese adventurers, Peng Jiamu and Yu Chunshun who went missing around Lop Nur in 1980 and 1996.

Lop Nur is now just another expanse of desert. In summer it reaches extreme temperatures and not a bird is to be seen in the sky. It is now known as the Sea of Death.

Lake Tai – the 100 billion yuan clean-up

The beauty of Lake Tai has long been praised in Chinese poems and songs. But by 2007 that beauty was all but gone. An algal bloom, poor water quality and a foul smell left residents of nearby Wuxi without clean drinking water for a week, resulting in widespread media coverage and panic-buying of bottled water.

Lake Tai lies between Jiangsu and Zhejiang, two of China’s most developed provinces. The Lake Tai basin covers 0.4% of China’s land mass, yet accounts for 8% of its GDP. The area is China’s most urbanised – and produces nine times more pollutants per unit of area than the national average. The pollutants pouring into the lake resulted in eutrophication, and then algal blooms.

The costs to local government were huge. As of 2014, government at all levels had spent a total of 96 billion yuan (US$14 billion) cleaning the lake, with another 116.4 billion (US$17 billion) to come.

But the approach to cleaning up the lake has also established a new model in China for similar problems elsewhere, making it possible to trade the right to release waste water. Jiangsu was also one of the first provinces to set up an environmental credit rating system for businesses.

Water quality has improved in recent years, but the risk of algal blooms remains.

But most of the country's lakes are in a state of crisis. China has a much smaller freshwater resource by population than many other nations, and those resources are both shrinking and threatened by pollution. Not only is China the world’s largest user of fertilizers, its water-polluting industries such as textiles and paper-making are huge, and both agriculture and industry have enormous water footprints.

Here, we include a couple of China’s traditional “five lakes” in the central and eastern parts of the country, but also include others that may not have the same cultural importance but which remain valuable ecosystems.

Click image above to explore China's lakes

Poyang Lake – to dam or not to dam

Despite being known as China’s largest freshwater lake, Poyang has no fixed size. The lake is huge, shallow and connected to the Yangtze, which means that every year its size fluctuates in line with the height of the river, shifting wildly from between 3,000 to only 100 square kilometres. For this reason it is known for becoming a wide expanse of clear water when in flood but little more than a river in the dry season.

But though Poyang shrinks during the dry season, it still provides a crucial habitat for migrating birds, which arrive here in autumn from Siberia to rest over the winter.

Yet for a decade now, Poyang has been experiencing earlier and longer dry seasons, and unusually low water levels. In extreme cases the locals have seen water supplies cut off entirely. Climate change is one reason, but the role of the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s biggest hydropower project, has also come in for scrutiny.

The office in charge of the lake’s water management system plans to build a barrier between the Yangtze and Poyang Lake to address the problem. But opponents say this will block migrating fish, and higher water levels will cause problems for the birds – resulting in ecological disaster. There is also a question over whether or not retaining more water in the lake will affect water security for cities downstream. The debate looks set to continue.

Qinghai Lake – back from rock bottom

Qinghai Lake is a saltwater lake situated in the north-east of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, and is China’s largest. But unlike other lakes that are shrinking, Qinghai seems to be recovering, with water levels increasing in recent years.

The provincial authorities have monitored the lake area since 1974, finding that in 2005 it had shrunk by 253 square kilometres, to 5.67% of its size in 1974. chinadialogue expressed concern about the risk to the lake a decade ago. But since 2005 the lake has, unexpectedly, been recovering. By 2016 it was almost back to its 1974 size, the largest recorded.

In February 2017 a provincial survey found the environment of the Qinghai Lake basin was well protected. The management bureau for the Qinghai Lake National Nature Reserve says that alongside interventions, such as returning farmland to forests and pastures and restoration of vegetation, another important factor is increased precipitation and glacier melt resulting from climate change. It’s ironic that while changing weather patterns are threatening low-lying islands and coastal areas, China’s largest lake is actually benefiting.

Ulunsuhai Nur

Situated in Inner Mongolia, Ulunsuhai Nur is home to 200 types of bird and is the highest wetland at this latitude. Strictly speaking, the lake is manmade, and was formed by efforts to redirect water from the Yellow River. Today, 80% of its water is directed through agricultural irrigation systems nearby, with the rest coming from rainfall.

From 1965 to 1975 local people constructed a modern drainage system between the Yellow River, farmland and Ulunsuhai Nur, to ensure water from irrigation would flow quickly into the lake where vegetation and microorganisms would break down fertilizer run-off. The “purified” water is then returned to the Yellow River.

That system of irrigation and drainage made the plains around Ulunsuhai Nur one of northern China’s most important agricultural regions, while the recovery of water from agriculture made the lake – which should be arid – a paradise for birds and a tourist hot spot.

But the system is today on the brink of failure. Experts point out that fertilizer use in China has increased 55-fold in 40 years, and Ulunsuhai Nur can no longer cope. For about ten years the lake has seen algal blooms during some summers resulting from eutrophication. This has worsened the water quality and affected the entire ecosystem, from birds to fish.

Lop Nur – the Sea of Death

Look down from the air and you can see the ear-like shape of Lop Nur, once a large lake but now dried up. In the 1920s it was estimated to be 3,000 square kilometres in size – twice as large as Beijing today. In 1959, it was still possible to sail a boat on it. It’s unclear when the lake dried up exactly, but the region is incredibly arid and once the rivers stopped flowing, Lop Nur, which was only three or four metres deep, may have dried up in a matter of years.

The lake has always had a legendary quality. Sven Anders Hedin, a Swedish explorer in the early 20th century, “discovered” it while travelling through the desert. Archaeologists later excavated relics and determined that it would have been an important oasis and stop on the Silk Road. It’s also claimed the lives of a number of explorers, including two famous Chinese adventurers, Peng Jiamu and Yu Chunshun who went missing around Lop Nur in 1980 and 1996.

Lop Nur is now just another expanse of desert. In summer it reaches extreme temperatures and not a bird is to be seen in the sky. It is now known as the Sea of Death.

Lake Tai – the 100 billion yuan clean-up

The beauty of Lake Tai has long been praised in Chinese poems and songs. But by 2007 that beauty was all but gone. An algal bloom, poor water quality and a foul smell left residents of nearby Wuxi without clean drinking water for a week, resulting in widespread media coverage and panic-buying of bottled water.

Lake Tai lies between Jiangsu and Zhejiang, two of China’s most developed provinces. The Lake Tai basin covers 0.4% of China’s land mass, yet accounts for 8% of its GDP. The area is China’s most urbanised – and produces nine times more pollutants per unit of area than the national average. The pollutants pouring into the lake resulted in eutrophication, and then algal blooms.

The costs to local government were huge. As of 2014, government at all levels had spent a total of 96 billion yuan (US$14 billion) cleaning the lake, with another 116.4 billion (US$17 billion) to come.

But the approach to cleaning up the lake has also established a new model in China for similar problems elsewhere, making it possible to trade the right to release waste water. Jiangsu was also one of the first provinces to set up an environmental credit rating system for businesses.

Water quality has improved in recent years, but the risk of algal blooms remains.

courtesy: chinadialogue

Comments