Greenpeace urges legal ban to tackle problem after finding that top personal care companies fell short on commitments, writes Damian Carrington

Tiny plastic beads are widely used in toiletries and cosmetics but thousands of tonnes wash into the sea every year, where they harm wildlife and can ultimately be eaten by people, with unknown effects on health. A petition signed by more than 300,000 people asking for a UK ban was delivered to the prime minister in June A US law banning microbeads was passed at the end of 2015.

The Greenpeace report surveyed the world’s top 30 personal care companies and found that even those ranked highest came up short of the standard they deemed acceptable.

One of the leaders, Colgate-Palmolive, said it stopped using of plastic microbeads at the end of 2014, but Greenpeace said the pledge only applied to products used for “exfoliating and cleansing”. Microbeads can be used in moisturisers, makeup, lip balms, shaving foams and other products.

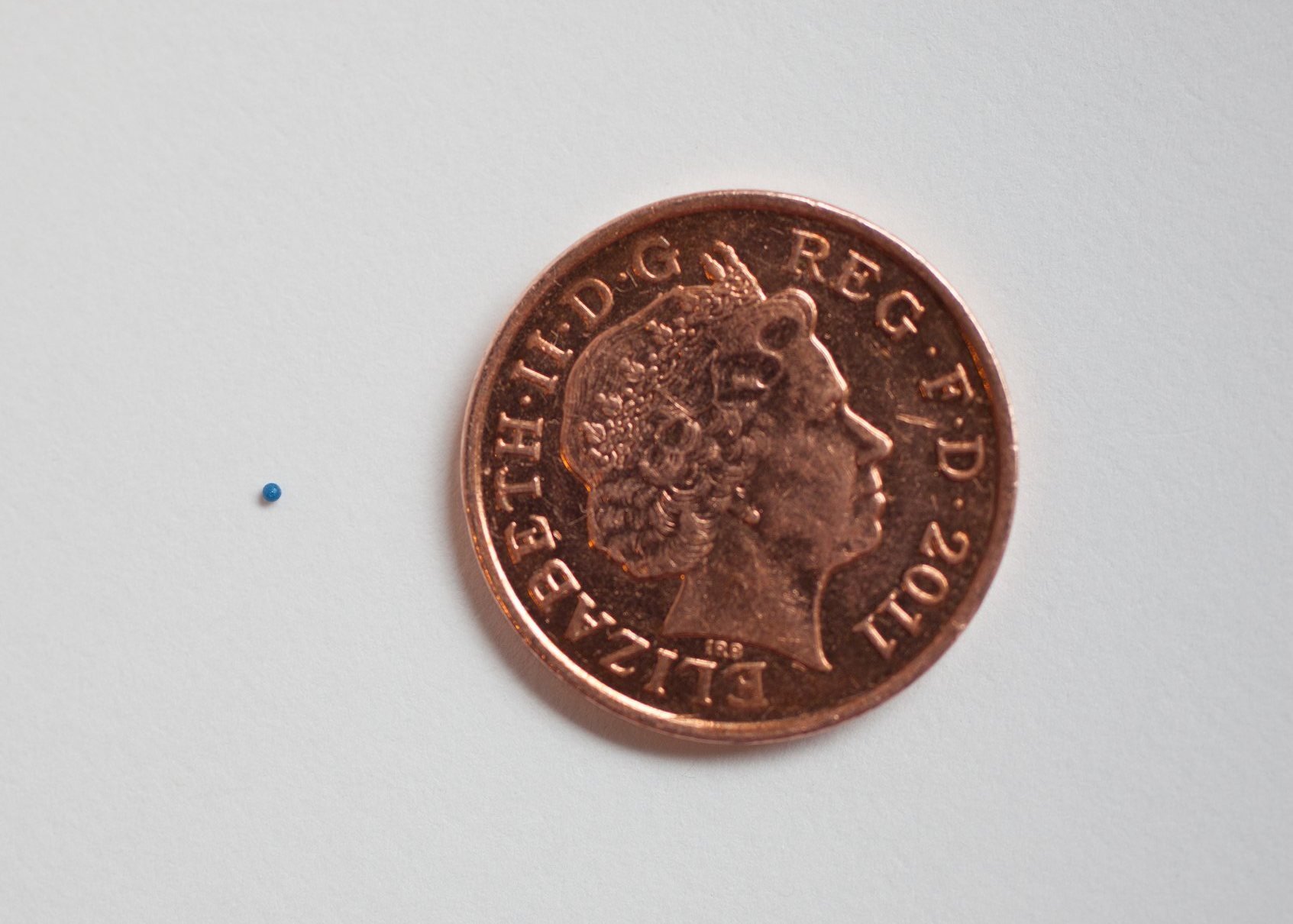

Microbeads are so small that they will not be filtered by sewage systems. Photograph: Vanessa Miles/Greenpeace

One of the lowest-ranked companies was Estée Lauder, which says it “is currently in the process of removing exfoliating plastic beads in the small number of our products that contain them”. Greenpeace said the company’s commitment is too narrow, applying only to microbeads used for exfoliating, and does not set a deadline.

The lowest-ranked company was US-based Edgewell Personal Care. It was given a score of zero out of 400 by Greenpeace, as “they did not respond to the survey and no publicly available information was found”. However, an Edgewell spokeswoman said: “We did not participate in the Greenpeace survey, as we do not incorporate the use of microbeads in any of our wide range of personal care products.”

The world’s biggest personal care company, Procter & Gamble, was ranked joint 18th. The company, whose brands include Olay, says its “goal is to remove polyethylene microbeads from all our cleansers and toothpastes by 2017”. Greenpeace said the commitment was unacceptable because it applies to just one type of plastic, rather than all types, and applies only to personal cleansing and oral care products.

Other loopholes in company pledges include not committing to phasing out microbeads in all countries, being unclear about the size of the microbeads excluded and allowing the use of “biodegradable” plastic microbeads, despite such materials being labelled as a false solution by the chief scientist at the UN Environment Programme.

Louise Edge, a senior oceans campaigner at Greenpeace UK, said: “When it comes to dealing with microbeads, companies are all over the shop,” said Louise Edge, senior oceans campaigner at Greenpeace UK.

“The UK government has already said it agrees that a ban on microbeads is the right way forward,” she said. “The new environment secretary, Andrea Leadsom, has some big challenges ahead of her, but banning microbeads would be a simple and effective start.”

Mary Creagh, the chair of the cross-party environmental audit committee of MPs, which will publish its inquiry into the issue in the summer, said: “Cosmetics companies’ voluntary approach to phasing out plastic microbeads is inconsistent and confusing for consumers. Most customers would be horrified to discover the effect their facial scrubs are having on the marine environment.”

Daniel Steadman, from Fauna & Flora International, which produces The Good Scrub Guide, said: “When you get down into the details of these brands’ microbead commitments, the potential for confusion is enormous. Marine life can be harmed by any type of plastic reaching our oceans, so if it’s a solid, a plastic and in a product that goes down the drain, it shouldn’t be there.”

Christopher Flower, the director-general of the UK’s Cosmetic Toiletry and Perfumery Association, said: “The cosmetics industry is taking this issue extremely seriously and is very much aware of its responsibilities to its customers and the environment.”

He said the European personal care association, Cosmetics Europe, has issued arecommendation to end the use of “synthetic, solid plastic particles used for exfoliating and cleansing that are non-biodegradable in the marine environment” by 2020.

“We believe that this course of action will have an impact far more quickly than waiting for any legislative ban,” said Flower He added that most microbeads are likely to have been phased out long before 2020.

Microbeads are too small to be filtered effectively by sewage treatment plants and flow into the oceans. Plastic pollution in the oceans is a huge problem: 5tn pieces of plastic are floating in the world’s seas. Microbeads are a small but significant part of this, which campaigners argue are the easiest to deal with.

Microbeads are eaten by marine life, which mistake them for food particles, and have been shown to kill fish before they reach reproductive age. The tiny beads can also attract toxins from seawater, which are then passed up the food chain.

The beads are thought to be eaten by people consuming seafood and possibly breathed in too. Safe alternatives are already available, including ground nutshells, pumice, sugar and salt.

Toothpaste containing microbeads. Small plastic particles such as these are used in many cosmetic products. Photograph: Georg Mayer/Greenpeace

courtesy:chinadialogue

Comments