Construction of Congo's Inga dam stumbles over stark environmental concerns, says Peter Bosshard

The Inga 3 Dam,

on the Congo River, is the first stage of a plan to build the world’s

largest hydropower complex, the 40,000 MW Grand Inga Dam.

Even though more than 90% of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) population has no access to electricity, the project will primarily generate power for mining companies and export markets, such as South Africa.

The World Bank and the World Energy Council have presented the Inga 3 Dam as a “dream for Africa”, and a model for the lessons learned from past mega projects. But the hydropower project on the Congo is unravelling into a political ploy that shows a disregard for the people and the environment that are affected.

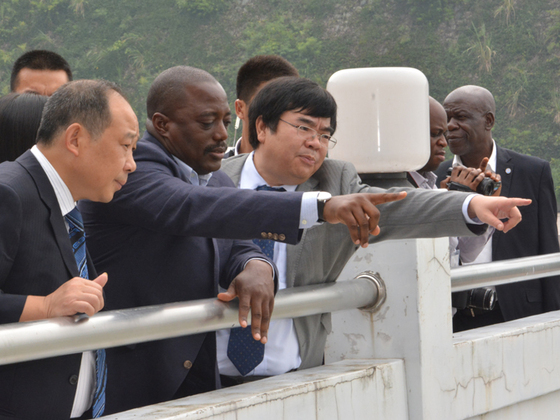

At the same time, the dam is proving an important test case for Chinese builders who are behind its construction.

In 2013 and 2014, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank approved US$141 million (928 million yuan) in grants for the preparation of the US$14 billion (92 billion yuan) project. Their grants included funds for a social and environmental impact assessment.

While the multilateral financiers did not address the questionable benefits of the mega project, they at least offered some assurance that Inga 3 would follow international social, environmental and anti-corruption standards.

Or would it? In September 2015, the Australian company SMEC won the contract to carry out the social and environmental impact assessments and the resettlement plan for the project. According to internal sources, the DRC government was not happy with the choice of company and refused to work with SMEC.

Under World Bank procurement guidelines, companies that bribe government officials are blacklisted; we can only speculate that government officials may not have received what they expected from the Australian company.

More than two years after the approval of the World Bank and AfDB grants the impact assessments for Inga 3 have still not begun. Yet in early May, Bruno Kapandji, the head of the Grand Inga Project Office, announced that the DRC government would select developers for the mega-dam within three months, and that construction would start by June 2017.

False urgency

The DRC government says that Inga 3 is under time pressure because the contract with South Africa, the main purchaser of the project’s electricity, will expire in 2021. The South African government may not be prepared to renew the contract after President Zuma, who promoted Inga 3 despite considerable opposition, steps down in 2019. But the South African contract alone does not explain the sudden haste.

Importantly, if the Congolese President Joseph Kabila wants to remain in power after his second term finishes at the end of 2016, which would violate the constitution, he may wish to appeal to vested interests who can make it possible. Signing multi-billion dollar contracts with the developers of Inga 3 might be one way of improving relations with the country’s power brokers.

Nature threat

Even though more than 90% of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) population has no access to electricity, the project will primarily generate power for mining companies and export markets, such as South Africa.

The World Bank and the World Energy Council have presented the Inga 3 Dam as a “dream for Africa”, and a model for the lessons learned from past mega projects. But the hydropower project on the Congo is unravelling into a political ploy that shows a disregard for the people and the environment that are affected.

At the same time, the dam is proving an important test case for Chinese builders who are behind its construction.

In 2013 and 2014, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank approved US$141 million (928 million yuan) in grants for the preparation of the US$14 billion (92 billion yuan) project. Their grants included funds for a social and environmental impact assessment.

While the multilateral financiers did not address the questionable benefits of the mega project, they at least offered some assurance that Inga 3 would follow international social, environmental and anti-corruption standards.

Or would it? In September 2015, the Australian company SMEC won the contract to carry out the social and environmental impact assessments and the resettlement plan for the project. According to internal sources, the DRC government was not happy with the choice of company and refused to work with SMEC.

Under World Bank procurement guidelines, companies that bribe government officials are blacklisted; we can only speculate that government officials may not have received what they expected from the Australian company.

More than two years after the approval of the World Bank and AfDB grants the impact assessments for Inga 3 have still not begun. Yet in early May, Bruno Kapandji, the head of the Grand Inga Project Office, announced that the DRC government would select developers for the mega-dam within three months, and that construction would start by June 2017.

False urgency

The DRC government says that Inga 3 is under time pressure because the contract with South Africa, the main purchaser of the project’s electricity, will expire in 2021. The South African government may not be prepared to renew the contract after President Zuma, who promoted Inga 3 despite considerable opposition, steps down in 2019. But the South African contract alone does not explain the sudden haste.

Importantly, if the Congolese President Joseph Kabila wants to remain in power after his second term finishes at the end of 2016, which would violate the constitution, he may wish to appeal to vested interests who can make it possible. Signing multi-billion dollar contracts with the developers of Inga 3 might be one way of improving relations with the country’s power brokers.

Nature threat

The Congo River has the second highest diversity in fish species

after the Amazon. The Inga 3 Dam would seriously impact these rich

fisheries but in spite of the ecological sensitivity, the DRC government

has not moved forward with an environmental impact assessment for Inga

3.

At a meeting with civil society groups in April, Bruno Kapandji argued instead that early feasibility studies (which didn’t assess environmental impacts in any detail) had found that the project would not have any negative impacts. And in a meeting in early May, the project director asked International Rivers and our Congolese partner CORAP whether NGOs couldn’t “commission or finance these studies.”

Chinese investment

Bruno Kapandji has made it clear that he hopes to award the Inga 3 contract to a Chinese consortium, and to build the project with Chinese funding. In early May he said that the Chinese companies would be able to complete the project in a “maximum of five years and if they’re free to do whatever they want to do they can even do it in four years.”

It is shocking that the world’s biggest hydropower scheme could go forward without an assessment of its social and environmental impacts.

The Chinese government has instructed its dam builders not to build any overseas projects without environmental impact assessments. The China Three Gorges Corporation and Sinohydro, members of the Chinese consortiums in question, have both committed not to build any projects without such assessments.

Building the Inga 3 Dam without carrying out thorough due diligence would seriously undermine the efforts of Chinese companies to strengthen their environmental track record internationally.

This raises questions. Will foreign policy interests – and particularly China’s mining interests in the DRC – trump financial and environmental responsibility? Is the Chinese government more interested in buttressing President Kabila and protecting its Congolese mining projects or safeguarding the reputation of its global dam builders?

Wherever the money comes from, one thing is certain, any investors who put $14 billion into a project whose main contract may expire before it is complete will make a risky bet. And any dam builders that support a mega-dam without social and environmental due diligence will establish themselves as substandard actors. The public spotlight will continue to be on Grand Inga.

At a meeting with civil society groups in April, Bruno Kapandji argued instead that early feasibility studies (which didn’t assess environmental impacts in any detail) had found that the project would not have any negative impacts. And in a meeting in early May, the project director asked International Rivers and our Congolese partner CORAP whether NGOs couldn’t “commission or finance these studies.”

Chinese investment

Bruno Kapandji has made it clear that he hopes to award the Inga 3 contract to a Chinese consortium, and to build the project with Chinese funding. In early May he said that the Chinese companies would be able to complete the project in a “maximum of five years and if they’re free to do whatever they want to do they can even do it in four years.”

It is shocking that the world’s biggest hydropower scheme could go forward without an assessment of its social and environmental impacts.

The Chinese government has instructed its dam builders not to build any overseas projects without environmental impact assessments. The China Three Gorges Corporation and Sinohydro, members of the Chinese consortiums in question, have both committed not to build any projects without such assessments.

Building the Inga 3 Dam without carrying out thorough due diligence would seriously undermine the efforts of Chinese companies to strengthen their environmental track record internationally.

This raises questions. Will foreign policy interests – and particularly China’s mining interests in the DRC – trump financial and environmental responsibility? Is the Chinese government more interested in buttressing President Kabila and protecting its Congolese mining projects or safeguarding the reputation of its global dam builders?

Wherever the money comes from, one thing is certain, any investors who put $14 billion into a project whose main contract may expire before it is complete will make a risky bet. And any dam builders that support a mega-dam without social and environmental due diligence will establish themselves as substandard actors. The public spotlight will continue to be on Grand Inga.

See video of International Rivers meeting with President Bruno Kapanji on May 9, 2016.

courtesy:chinadialogue

Comments