Is the World Bank’s climate spending quantity over quality?

The World Bank’s recent decision to increase funding for climate-friendly projects masks deficiencies, writes Margaret Federici

Ahead of its Spring Meetings, which ended on April 17, the World Bank released a Climate Change Action Plan (CCAP) that sets out the institution’s work on climate change from now until 2020, the same timeframe guiding the Paris Agreement.

By 2020, the Bank hopes to provide US$29 billion (187.4

billion yuan) for climate projects, nearly triple its current

average per year. This would increase the percentage of Bank funding for

climate from 21% to 28% of its total portfolio.

Directing 28% of the Bank’s budget towards climate action could do a lot to reorientate capital markets towards renewables, support sustainable urban infrastructure and strengthen the resilience of communities vulnerable to climate disaster.

Unfortunately the old adage ‘quality over quantity’ may apply here. For one, the CCAP repeatedly references hydropower as a renewable. Large hydro has a long and complicated history at the Bank. The Narmada Dam and other movements called global attention to the displacement, lost livelihoods and irreversible environmental impacts that dams cause.

Directing 28% of the Bank’s budget towards climate action could do a lot to reorientate capital markets towards renewables, support sustainable urban infrastructure and strengthen the resilience of communities vulnerable to climate disaster.

Unfortunately the old adage ‘quality over quantity’ may apply here. For one, the CCAP repeatedly references hydropower as a renewable. Large hydro has a long and complicated history at the Bank. The Narmada Dam and other movements called global attention to the displacement, lost livelihoods and irreversible environmental impacts that dams cause.

Yet over the past several years, the Bank has

returned to promoting mega-dams as a green, affordable option for

getting power to the poor, promising it can get large hydro ‘right.’

In December 2015, 500 organisations from 85 countries signed onto a Civil Society Manifesto for the Support of Real Climate Solutions to keep large hydro out of climate finance.

In December 2015, 500 organisations from 85 countries signed onto a Civil Society Manifesto for the Support of Real Climate Solutions to keep large hydro out of climate finance.

They cite a number of reasons, including that dams disrupt

rivers’ natural function as carbon sinks and do massive damage to

freshwater ecosystems. Perhaps most compelling is that mega dams rely on

a central grid, so their potential for providing rural electrification

is low. This means that the energy they produce is more likely to go to

large industrial projects than to the poor.

Another area of concern in the World Bank plan is its treatment of forests. The CCAP notes that between 2002 and 2015, the World Bank Group has financed US$15.7 billion (101 billion yuan) in projects with forestry components.

Another area of concern in the World Bank plan is its treatment of forests. The CCAP notes that between 2002 and 2015, the World Bank Group has financed US$15.7 billion (101 billion yuan) in projects with forestry components.

A recent study shows, however, that development finance for forests is less than 3% of the total annual portfolio for the IBRD/IDA,

which includes concessional finance for the poorest borrowing

countries. This begs the question of what indigenous and

forest-dependent communities will ‘net’ from World Bank investment in

forests vis-a-vis its investment in sectors that drive deforestation

like energy, mining and transport.

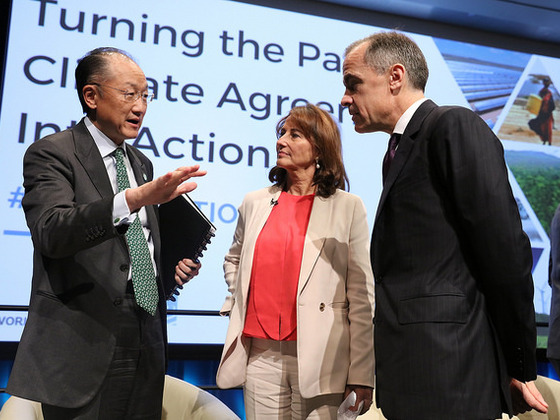

The CCAP promises that “WBG organisation is now aligned to deliver on climate change". While top-level Bank officials may be poised to take on climate challenges, at least with their discourse, questions remain around the readiness of their counterparts at the operational level.

Often, screening projects for climate impacts takes the form of ‘toolkits’ and ‘guidance notes’ for discretional use by project task teams. These documents tend to focus more on climate impacts to the project than how the project itself would affect the resilience of climate-vulnerable communities and ecosystems.

The CCAP promises that “WBG organisation is now aligned to deliver on climate change". While top-level Bank officials may be poised to take on climate challenges, at least with their discourse, questions remain around the readiness of their counterparts at the operational level.

Often, screening projects for climate impacts takes the form of ‘toolkits’ and ‘guidance notes’ for discretional use by project task teams. These documents tend to focus more on climate impacts to the project than how the project itself would affect the resilience of climate-vulnerable communities and ecosystems.

Furthermore, the linchpin for real climate action at

the World Bank is assessment of alternatives. The Bank should require

greenhouse gas emissions accounting for the full life cycle of projects

before they are approved, to determine the social costs of carbon and

whether they warrant a look at alternative project models.

While the value of up-front assessment seems self-evident, the World Bank Board has thrown its support behind Bank Management’s new ‘adaptive risk management’ strategy, which narrows the scope of the Bank’s required due diligence and allows borrowing countries flexible time schedules for identifying and addressing environmental and social risk.

While the value of up-front assessment seems self-evident, the World Bank Board has thrown its support behind Bank Management’s new ‘adaptive risk management’ strategy, which narrows the scope of the Bank’s required due diligence and allows borrowing countries flexible time schedules for identifying and addressing environmental and social risk.

This means that even a climate safeguard

could prove spineless in preventing carbon-intensive projects from

reaching a Board vote. This has serious implications, especially given

the Bank’s ongoing consideration of the $40 million Kosovo C lignite coal-fired power plant.

What’s more, World Bank lending through policy loans are subject to far fewer requirements for environmental and social assessment, and would not even be covered by the proposed climate safeguard. This risks World Bank funds going to support policies and subsidies that incentivise fossil fuels – yes, even coal – thereby cementing carbon-intensive development paths for countries whose poor will be hardest hit.

While the potential of the Bank’s target 28% towards climate initiatives is commendable, the real question is: how will the Bank ensure that the other 72% of its portfolio meets the standards set by its lofty climate goals?

What’s more, World Bank lending through policy loans are subject to far fewer requirements for environmental and social assessment, and would not even be covered by the proposed climate safeguard. This risks World Bank funds going to support policies and subsidies that incentivise fossil fuels – yes, even coal – thereby cementing carbon-intensive development paths for countries whose poor will be hardest hit.

While the potential of the Bank’s target 28% towards climate initiatives is commendable, the real question is: how will the Bank ensure that the other 72% of its portfolio meets the standards set by its lofty climate goals?

Courtesy:chinadialogue

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home